It is a truth which should be universally acknowledged that the most important skill for a customer-facing job in what we laughingly call “information technology” is a cast-iron ability to say no—and make it stick.

The misguided desire to please other humans by attempting to deliver on their every request has sunk more projects than any units mismatch or catastrophic misconfiguration—even more than the justly feared Friday afternoon deployment.

The key to success is an agreed definition of what success is, and how we will all know and measure whether we have achieved it. Let’s take the car as an example.

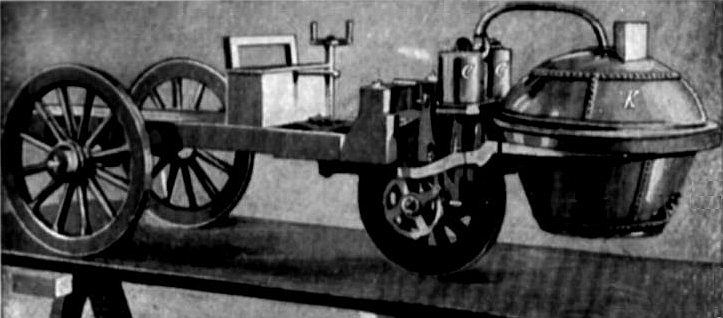

French Cars Have Always Been Weird

These days, we would consider a car to be woefully unfinished if it were lacking upholstered seating for at least four adults, a roof and windows to keep the elements out and some form of in-car entertainment—an FM radio as a bare minimum, probably a CD slot or USB socket as well. This is on top of seat belts, airbags, anti-lock brakes that are probably power-assisted and more lights and safety features than you can shake a stick at.

Nicolas Cugnot did not bother with any of these features. His design didn’t even have four wheels. It not only didn’t have an airbag in the steering wheel, it didn’t even have a steering wheel. It was controlled with a ridiculous tiller arrangement that unsurprisingly completely failed to catch on. And yet, his vehicle was a success by the stated criteria of the project: It made it much easier for the French army to haul ammunition around.

Admittedly, he was also lucky enough to be constrained by the technology available to him. Even Louis XIV might have balked at adding a four-piece chamber ensemble to provide an appropriate musical soundtrack for the driver. But the key point is this: Monsieur Cugnot stuck to his brief, and concentrated all his efforts on the features necessary to achieve it.

Bringing Apple Into It

In somewhat more recent times, we have Steve Jobs (emphasis mine):

People think focus means saying yes to the thing you’ve got to focus on. But that’s not what it means at all. It means saying no to the hundred other good ideas that there are. You have to pick carefully. I’m actually as proud of the things we haven’t done as the things I have done. Innovation is saying no to 1,000 things.

One reason why Steve Jobs is so famous is that he actually said those thousand nos—often loudly, rudely and profanely. Steve stands out in IT because most technologists have an irrepressible instinct when faced with a question to start to speculate about it, bikeshed possible solutions, build a quick minimum viable prototype and, before you know it, you are armpit-deep in feeping creatures, all of which you are now somehow responsible to nurture and feed. Not being a technologist himself but more of an ideas person, Steve was perhaps better able to take a step back and focus on the end goal.

Let’s Get Concrete

Now, this should not be taken as a license to adopt all of Steve Jobs’ methods (Lesson One: Be a complete arsehole to absolutely everyone in your life), if for no other reason that even Steve got fired for it, and from the company he founded at that. When someone comes to you with a request for just one leeeeetle feature, you and I probably can’t get away with screaming “NO!” and slamming the door in the requester’s face. The polite and career-prolonging way to deal with the problem is to ask, “Why?”

Ideally, in the process of explaining the rationale for whatever the request is, some other solution to the problem will be identified. A good way to improve the odds of this happening is to involve other people in the discussion. Extending the audience in this way creates opportunities for someone to interject helpfully with something along the lines of, “but Carol, we have a perfectly good hammer over there; why are you trying to use a screwdriver to batter a nail in?”

Sometimes, you may need to adopt an iterative approach, which sounds impressive, but simply means waiting until the end of the first explanation, nodding thoughtfully, and then asking, “Yes, but why?” Among people who watch more television than me, this is known as the Columbo approach: “Help me understand, what is it you are trying to do here?” and just keep doggedly repeating the question. Eventually enlightenment will arrive—or the requester will get tired and go away, which is also a perfectly valid win condition.

This method will also help with the tricky situation where the most important question is the one which is not being asked. There is often an implicit question behind that one, where the solution is not to give a glib answer, but to think critically about the proposed or effective solution and ask the questions yourself: “Why are we trying to solve for this?” Or, “What is this thing you are proposing actually meant to do?” And finally, “What was the original problem, anyway?”

People have a tendency to focus on the issue that is right in front of them, even when the real problem is in an upstream step of the process. They observe or experience something about X as the identified problem, and so default to solving for X directly without considering the broader landscape. This leads to convoluted, inefficient and often high-friction solutions—Rube Goldberg/Heath Robinson machines (delete as appropriate to whichever side of the Atlantic you are on), where a simple connecting pipe is all that is required. An artillery piece will make holes in the ground, but there are a couple of collateral impacts you may want to consider—and maybe offer a spade instead.

Unfortunately even the Columbo Method is not entirely guaranteed to work, because on some rare occasions the underlying request is actually valid and cannot be summarily dismissed. This is when you bring out the big guns and start ranking the urgency of what was already agreed as the scope of the project (a nail hammered into the wall sturdily enough to support that lovely picture) as opposed to what is being requested (a fully motorized picture rail, capable of supporting up to 10 paintings on the scale of Guernica and turning them to optimize lighting conditions throughout the day while also keeping them out of direct sunlight). Nobody is saying that the second option would not be nice, but it certainly won’t be done in time for supper.

And that, children, is how you say No. Go forth, and do ye likewise, and may all your projects be huge successes. And, most importantly, not require me to come in and clean up after you.